Editor’s Note: Since this post’s publication, we’ve further improved our approach to distributions. Find a revision to our Rainy Day Fund here, and continue reading Great Not Big as we tinker with and evolve our model.

Why own shares in a company with a goal of being 100 years old? You definitely shouldn’t be hoping for a big payday when the company gets acquired. While there are non-financial benefits of ownership, the decision to buy is a financial one, and thus there should be a financial return to shareholding. In our program, that reason is distributions. This post describes the philosophy and mechanics behind what we do with our profits.

This post is the fifth in a series on Atomic Object’s ownership and the non-ESOP approach we took to gradually shift from a founder-owned to a broadly employee-owned company.

- Context, motivations, accomplishments to date

- Description of our Approach: Atomic Plan and ESPP

- Valuation

- Financing

- Distributions

- Lessons Learned

- Perspectives of Founders and Employees

- Alternatives and Unsolved Problems

Philosophy

When I created our non-ESOP employee ownership program, I wanted share ownership to be a positive thing for my younger colleagues from the moment they bought in. I wanted to encourage Atoms to stay around the company for a long time, but I also wanted them to benefit immediately and consistently over time from their shares. The solution I came up with was a 10-year vesting period for capital appreciation and quarterly distributions of profits.

The first goal in our early years was building up a rainy day fund. While we shared profits with employees from the start, all of the remaining profits went to building our cash reserves. The return on those profits was my peace of mind. After a shocking first-year tax bill (we’ve always been a pass through entity, so retained earnings show up as income for owners), we got more sophisticated about distributing at least enough to pay the taxes on our retained earnings.

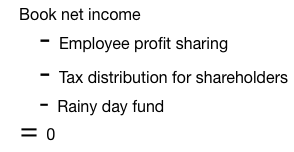

In hindsight, it would probably have been better to start as a C corp, build the rainy day fund, then convert to an LLC or S corp. The simple diagram below describes the distribution of our profits in the first few years. After employee profit sharing, tax distributions, and rainy day fund contribution, there wasn’t anything left for share distributions.

When we reached the milestone of having three months of expenses in cash reserves, we started distributing remaining profits to shareholders (at the time, the two co-founders). The capital requirements of our service business were minimal, and there didn’t seem to be a reason to hold more cash than three months of burn. Over time, we found investment opportunities, and we gradually developed our philosophy of looking at our profits as something we could either re-invest in the company, invest in other companies, or distribute. Employee profit sharing fits into the re-investment bucket.

Profit Distribution Today

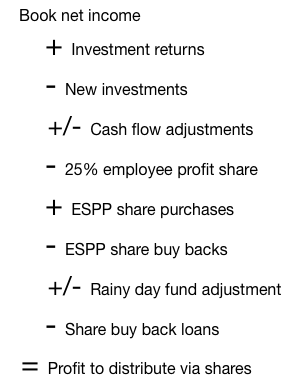

Nowadays the waterfall that determines where profits end up is a bit more complicated. The figure below shows how we start with book net income to get to the amount to distribute via shares.

When past investments pay off, we add those returns to the pool. We then subtract any new investments we’re making. We do some earnings smoothing (cash flow adjustments) when we see unusual and large expenses on the horizon.

We long ago formalized through convention the sharing of 25% of the pool to employees via a 5% 401k PS plan and a 1/N cash bonus (where N is the number of people in the company). I’ve come to see this 25% commitment as having given away 25% of a profit interest in the company to a theoretical entity known as “current employees”.

The next step in the waterfall is money that comes in from Atoms purchasing shares through our ESPP program. Since those shares are activated from a dormant pool of shares, this increases the total share count. The money from these sales is then distributed to shareholders, making it in effect a mandatory pro rata sale of a portion of everyone’s ownership interest. When people leave the company and these ESPP shares are bought back, that money comes from the shareholders and the shares are destroyed, lowering the share count.

The rainy day fund still needs to be maintained at the proper size, so if we’re growing, we subtract money from our profits to add to our cash reserves. In the rare quarters when we’ve contracted, we actually reduce the rainy day fund and distribute the extra money to shareholders. (More on this below.)

Lastly, if we have exercised our option to buy back a departing shareholder with a promissory note, we make those loan payments from the profit pool.

The profit that remains at the bottom of the waterfall is then distributed through shares.

Financial return

Over the 10 years of our employee ownership experience, the first year dividend yield on share purchases have averaged 17.8%, with a low of 10.4% and a high of 26.2%. The low occurred when we bought and renovated a building for our Grand Rapids office. The high occurred when we had an unusually nice payout from a prior investment.

In contrast, even the earliest participants in our plan, who are just now hitting their ten year vest for capital appreciation, have only see a 12% IRR on the value of their first share purchases. While that’s a pretty good return, it’s still quite a bit below the value of having gotten the dividend on those shares over the years.

Mechanics

Profit distribution is a somewhat complicated process. Some of the details we’ve figured out over the years are described below. We make sure to educate all shareholders on the mechanics of our approach.

Decision making

The managing members of the LLC (me, Mike Marsiglia, Shawn Crowley) act as the investment committee. Mike, wearing his CFO hat, decides on cash flow adjustments to smooth earnings.

Rainy day fund maintenance

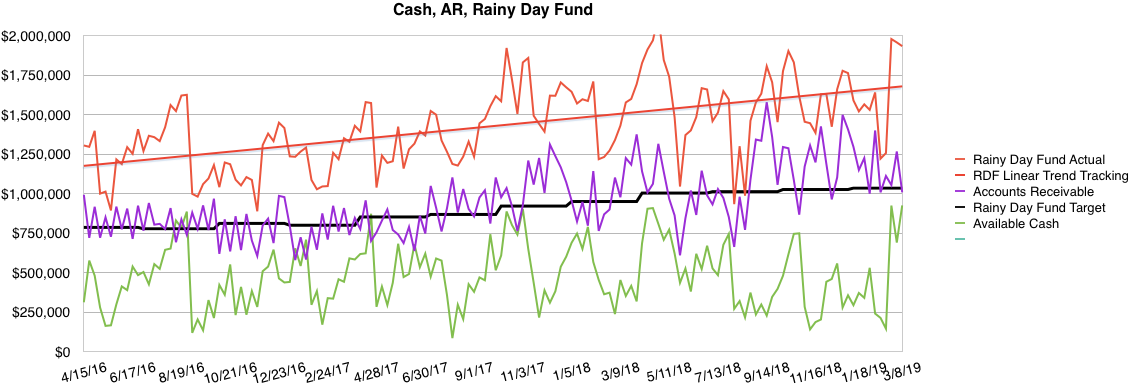

We define our rainy day fund to be the sum of cash in the bank and our accounts receivable. Our rainy day fund target was originally 3 months of full expenses. Eventually, we moved to 1.5 months as we gained confidence in our client diversification strategy, as well as the consistency of the demand for our services.

It’s easy to calculate monthly burn. We do some averaging of cost of people and expenses, then multiply by 1.5x to get the rainy day fund target amount.

What isn’t easy is to actually measure the current size of the rainy day fund. While it’s easy to check AR and the bank balance, it’s harder to know about accounts payable and accrued expenses. Without good knowledge of those, we may in effect not have as much money in the rainy day fund as we might think. The current level of cash reserves can also change day by day as bills are paid or come in.

We resolved this problem by simply declaring the rainy day fund to be full, and then switched to what I call a dead reckoning approach to keep it that way. Every quarter we measure whether our monthly burn has gone up or down compared to the past quarter, then we either add or subtract that difference from the quarter’s profit and retain more cash or distribute more profit. The key insight that resolved the messy business of measurement was that we really cared about the changes we should be making to our cash reserves, not its absolute value on any given day.

The graph below show three years of tracking the rainy day fund level (red line), the RDF target (black line), accounts receivable (purple line), and cash (green line).

Notice that the trend line on the RDF shows a consistent upward trend. This has to do with a “leak” we have that causes money to build up in the company because it doesn’t flow through the profit distribution waterfall. We periodically distribute extra money to shareholders and reset the RDF.

Notice also that the actual RDF and the trend line are well above the RDF target. This results from executing the RDF adjustment algorithm approximately one month after the close of the quarter. During the course of that month roughly the first third of the next quarter’s profit has accumulated. In effect this means our target of 1.5 months of expenses in the RDF is consistently more like 2 months.

Frequency of distributions

We like quarterly distributions because it fits well with our open-book management practice. We see results for a quarter soon after the quarter ends and can thus more easily correlate events in the quarter, and efforts made by all of us, with profitability and profit sharing.

If our performance was more seasonal, or our quarters more variable, quarterly distributions might not work. For example, distributing profits on Q1 and Q2 only to find that Q3 and Q4 were losses would put the company in a difficult spot, with no easy recourse. Without a strong and consistent track record (we haven’t had a quarterly loss since 2003) we’d probably use an annual profit distribution approach.

Tax distributions

Each quarter our accountant computes a minimum amount we need to distribute to cover pass through taxes of shareholders. We always distribute more than this amount, so it serves only as a safety check.

Timing gotchas

To do quarterly distributions required that we have accurate quarterly results. That, in turn, required us to get better at handling quarter boundaries of payroll and invoicing. See my earlier post on how we do this.

We have run into tricky situations when a year has seen unusual variations of profit between quarters as well as significant changes in ownership. Problems arise when the earnings attributed to a shareholder on the K1 statement at the end of the year represent an average for the year, but the distributions that have already been made are tied to share count and profits for each quarter.

Accrual results

We track our financial performance on an accrual basis. We also distribute profits on those accrual results. This means that if we have bad AR and write it off, we may already have distributed both employee profit sharing and share distributions on invoices we never collected. This happens rarely enough for us that it’s not a huge problem, and we do take an adjustment in a future quarter if necessary. Some inequity may arise if the body of employees or shareholders has changed between the time of distribution and adjustment.

Investment returns

The guideline we’ve developed for investments is to make investments out of book net income, i.e. before the 25% employee profit sharing. If the investments provide a return in a period of time fairly close to the investment period, we also bring the returns into the top of the waterfall. In one case we have had a significant investment return occur 11 years after the investment was made. For that case, we decided the most fair thing was to distribute that money only to shareholders and bypass the 25% employee profit sharing stage.

Conclusion

Our approach has been created and evolved over time to work well for us. Some of the ways we do things wouldn’t work very well if these things weren’t true:

- we can easily manage our regular capital needs from cash flow,

- our financial results are stable and predictable,

- we don’t have significant seasonality in our revenue or earnings,

- we have a very, very low rate of bad AR,

- and we’re consistently profitable.

- Attention: Spending Your Most Valuable Currency - February 10, 2022

- Slicing the Revenue Pie in a Multi-Stakeholder Company - July 30, 2021

- Commercial versus Existential Purpose - July 19, 2021

- How I Misunderstood Mentorship and Benefited Anyway - June 16, 2021

- Sabbath Sundays and Slow Mondays - June 4, 2021