Our non-ESOP approach to employee ownership meant we got to determine how our program worked. The legal advice we got was very helpful, but it didn’t tell us how our program should work, it just made it legally responsible. The overall success of the program says we got a lot of things right. But there were also things we didn’t anticipate, and quite a few things we’ve learned over the last 10 years. This post is a collection of those lessons learned, organized into the themes of Plan Design, Financial, Implementation, Legal, and Taxes.

This post is the sixth in a series on Atomic Object’s ownership and the non-ESOP approach we took to gradually shift from a founder-owned to a broadly employee-owned company.

- Context, motivations, accomplishments to date

- Description of our Approach: Atomic Plan and ESPP

- Valuation

- Financing

- Distributions

- Lessons Learned

- Perspectives of Founders and Atoms

- Alternatives and Unsolved Problems

A caveat for this entire post is that many of these things are my opinions, observations, and best guesses. There’s some stuff you can’t prove, and I certainly haven’t run a controlled experiment. On some of the points below, I state things with a certainty that’s impossible to prove, but handy to claim. Please take this as a blanket disclaimer; it saved me a bunch of typing.

Plan Design

Shares don’t create an ownership attitude

Ownership amplifies existing, desirable behavior. It doesn’t create it. Like compensation, if people feel they aren’t treated fairly, shares or money can be a huge de-motivator. But the reverse isn’t true. Neither shares nor money can create in people what most company founders really want. Employee ownership won’t create a culture of ownership, but it can amplify one. I also believe that pride of ownership helps people get through hard times when they may otherwise be tempted to leave or at least look around.

Sell, don’t give

We didn’t need the capital that share sales could have raised. But pricing at a significant discount to market and giving people the opportunity to buy is a key, positive trait of our approach. People value what they pay for. They give more serious consideration of the program when they buy. They educate and coordinate with their SO when they have to write a check or take on a loan.

A big consideration for selling over giving was that we didn’t start our program until we were 8 years into the company. A lot of value had been created at that point. A lot of risks had been taken. A new company with no profits or a lumpy history of profits is a different beast than Atomic in 2009.

Build your own valuation

Building your own valuation model lets everyone understand how you value the company. They can play with the levers in your model to see how the value responds to changes in key parameters. It helps educate new owners on what makes the company valuable. It’s a big part of what builds the confidence needed to create a transaction. Building your own model is a first principles, compositional, historical approach. Projections for the future are clearly visible.

There is an easier alternative: pick a multiple of revenue or EBITDA. I call this the lazy approach to valuation. With smaller, privately held companies these multiples are hard to come by. They are also really hard to justify on a first-principles basis. Good luck defending your magic number should someone want to understand the valuation it generates.

We recently faced a situation that showed the advantage of having built our own model. The tax reform of 2018 impacted our valuation in a couple of ways:

- The tax rate on pass-through profits decreased

- Some significant business expenses were no longer deductible

Working to understand and adjust our model was rather complex. But at least it was something we could do. If all we’d had to play with was a multiplier of revenue or profit, there’s have been absolutely no way to make a reasoned adjustment.

Hiring a valuation firm is another approach. I don’t have much experience with this. My impression is I’d have gotten something similar to what I created myself. Where I expect it would fall short is in the depth of my understanding and the business lingo used that Atoms would probably not be familiar with.

It is interesting to gather market data points to compare your valuation to. We like to keep an eye on how much our valuation is discounted against the market.

We have found some significant bugs in our model over the last 10 years. As we found them, we fixed them, but we didn’t try to go back in time and change transactions. Perhaps the best approach of all is to build your own model then have it carefully reviewed, both in concepts and implementation, by an expert.

Don’t trap people

I’ve heard stories of ESOP companies and people with jobs they no longer cared for sticking around just for the payout or the year’s contribution. The last thing I wanted was shareholding to prevent people who were unhappy from leaving. There is, of course, a tradeoff here with the point I made above: ownership can get people through hard times.

Focusing the financial value of shares on the distribution, not capital appreciation, helps avoid the golden handcuffs problem. In our plan, you own the shares upon purchase and get distributions from day one. If you leave your shares are bought back at what you paid for them. If you stay a really long time (10 years after first purchase), then you may also see a capital appreciation. But that’s not the only way to benefit financially.

I don’t believe anyone’s ever stayed at Atomic due solely to their owning shares. When people leave before 10 years they seem to really appreciate the check for their buyback, even if it’s just the money they paid to buy the shares.

Expect some buyer guilt

Atomic’s culture is an example of Bob Quinn’s notion of social excellence. People are close, care about each other, support each other, work together, socialize together, and respect everyone. Titles are minimal, distinctions between jobs or seniority few, and success is a team phenomenon. In a place like this, when people get a chance to buy shares, and others haven’t yet, you can expect some funny feelings. It reminds me of survivors’ guilt: why me? do I deserve this? why not the person I’m working next to?

Language matters

The notion of ownership is fine. Using that word for your program or to describe culture is great. The word “owners” is very different. In some contexts, “owner” has a certain mildly negative connotation. It encourages the “us/them” dichotomy of “employee/owner”.

I don’t think “employee” is a problematic word, though we prefer “Atom”. If you use employee, use it for everyone at the company. We switched to “shareholder” when I figured out the problem with “owner”. We’re all employees; some of us are shareholders.

Eligibility

Consider eligibility criteria very carefully. We originally had full-time employment as a requirement for shareholding. We hadn’t considered the case of someone transitioning to a part-time role with the company to balance work and family. Think of people who you might not yet employ.

We require five years of service before a significant purchase of shares. That’s been a good filter for us. Those who aren’t a good match, or whose life takes them away from Atomic, don’t become shareholders. On the other hand, five years is a long time for a new graduate. Maybe we could get the same level of confidence in someone and filter out early fails with three years.

Don’t believe that all millennials are job hoppers.

Criteria for offers

Strategic offers

The history of our efforts to channel growth into new offices, rather than continuing to expand the first office, brought up a steep disparity between ownership. If we’d stuck to the established criteria of five years of tenure before receiving an offer in the Atomic Plan, our new offices would be drastically underrepresented in the shareholder list.

I made the decision to offer share purchases strategically to managing partners and senior makers in our newly established offices. While I think this contributed to our eventual success in our Ann Arbor office, it wasn’t popular or appreciated by some folks in our original office who’d waited, or were still waiting, for five years to elapse to receive an offer.

If you use share offerings strategically, expect some people to be upset.

Financial

Ownership vs compensation

My view has always been that compensation is tied directly and only to the market and the job you do. Ownership is a wealth-building opportunity earned through contributions, position, and tenure. But it’s all money in the end, so it’s easy to confuse the two.

Shareholding is a crude tool to use for compensation. You can’t easily adjust it if someone changes jobs. Distributions from shares could easily push people well past market value for the job they do. Owning shares doesn’t change their job or how they do it.

My compensation as CEO was approximately 1.4x our top maker salary, 2x the average across the company, and 4x our lowest-paid employee. These modest ratios were consistent with our culture and supported by what we determined the market paid for various jobs. With the ownership distributions of my founder shares included (4-5x my compensation), those ratios became 8x, 12x, and 25x. Still well below 21st-century American excess, but out of alignment with Atomic’s culture, values, and the job market. The point is that my distributions from my founder shares had everything to do with starting the company, working hard, sacrificing, taking risks, being lucky, and nothing to do with my responsibilities as CEO. Seven Atoms had distributions from shares in 2018 that exceeded 50% of their salary.

Dividend versus capital appreciation

If you’re not building a company to sell it, then you should be striving for profitability. Correspondingly, the main reason to own shares becomes distributions or dividends. Unfortunately the media attention today mostly goes to growth stocks and startups built for exits, so people tend to think about capital appreciation and a single payoff as the point of shareholding. You need to do a lot of education to counter this popular conception.

The first participants in the Atomic Plan offering of 2009 saw a 13% annual capital gain in their first investment. That’s nice but pales compared to the 35% IRR they’ve seen between capital gains and dividends.

If you’re not seeking to sell, no one should be investing for that outcome. Long term employees should justly share in the growth in the value of the company. But in the meantime, and for those who buy shares but don’t achieve a very long tenure, the main financial benefit of ownership is distributions. Atomic uses a 10 year period to vest into capital gain appreciation rights.

You can finance it yourself

While it’s easy to outsource the loan management aspect of an employee ownership plan to a bank, for example, we’ve also found it very feasible to manage this internally. It’s worked well for us to separate the management of the loan program from the lender (me).

Be careful that terms on your loans don’t discourage employee-owners from embracing investment for the future. If they have loans with fixed terms and monthly payments and are counting on distributions to help make those payments, they may feel pressure to optimize for short-term profits and oppose longer-term investments.

Non-core business assets

If you make investments within the company, whether it’s real estate or startups, you may find success in that area begins to distort the valuation of your company. At one point, our ownership in a company we co-founded approached 40% of Atomic’s total valuation. That fundamentally changed the nature of investing in Atomic through share purchases by Atoms, since the risk profile of the venture-backed software startup was very different from our core service business. In effect, we had non-accredited investors indirectly purchasing an interest in a risky software startup.

Eventually, the building we purchased for our Grand Rapids office will have a similar effect on our valuation. As the mortgage is paid down, and/or the property appreciates, this investment will represent a significant asset in our valuation model.

These non-core business assets aren’t influenced by Atoms in general. They also aren’t productive in the sense that they throw off dividends as the core business does. If they come to represent a significant fraction of our valuation it will be harder for Atoms purchasing shares to amortize their ownership loans.

Investment payouts

When we make investments from the company, we do so with the money we’d otherwise be distributing via profit sharing or share distributions. The managers of the LLC make specific investment decisions and the more general decisions of capital allocation. This part of our investment strategy is consistent across all of our investments.

When our investments pay off, we see more variability in deciding what to do with that money. When the payoff happens relatively close in time to the investment, and the payoff comes in smaller amounts or over time, we put that money through the same profit-sharing algorithm that we use for our operational profits. This means all employees share 25% of the pay off through profit-sharing, and shareholders get 75% of the payoff. Examples of these sorts of investments have been a royalty and a venture fund investment.

When an investment takes a long time to pay off, we have faced a trickier situation. In one case, the pay off was substantial ($1.4M) and happened 11 years after the initial investment. There were only 10 Atoms around in 2018 who were also around in 2007 when the investment was made. The other 55 employees had joined after the investment period. To complicate it further, the value of this asset over the course of 9 years of Atomic Plan share purchases had risen dramatically. For the earliest employees the return on this investment was 11x over 11 years. For the most recent share purchasers, the investment was break-even. We decided in this case that the right thing to do was to distribute all of the pay off through shares and not apply the operational profit sharing of 25%.

Our ESPP pool was plenty large

When we first set it up in 2013, we reserved 10% of the outstanding shares for future activation as Atoms purchased shares through payroll deduction. Six years later we still have 8.8% of those shares left to activate. The initial maximum purchase allowance of $2,000 per year, and the natural turnover of shares as people departed meant the original 10% would last much longer than we anticipated. We increased the maximum amount to $4,000 a few years ago.

Currently, the ESPP has 59 eligible participants (greater than 1 year of service), 25 people participating, and 15 putting in the maximum of $4,000 per year. Assuming the company stops growing the participation rate remains constant, and no ESPP shareholders leave the company, the pool of inactive shares reserved for the ESPP will last approximately 15 years. I think in practice what this means is that the 10% pool will last indefinitely.

Blending profit sharing with share distributions

Our profit-sharing scheme (25% of net margin to all employees through 5% 401k PS and 1/N cash quarterly bonus) predates by about 5 years our employee ownership plan. While it’s not legally based, the convention of 25% profit sharing is so well-established that it would be difficult and highly disruptive to change.

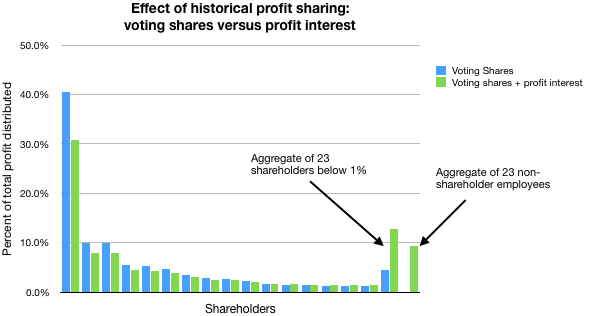

What I didn’t realize at the time of instituting the profit-sharing scheme was that by convention we had committed a 25% profit interest (not ownership) to the logical entity of “all current employees”. This has an impact on company valuation, as it reduces the number of distributions through shares by 25%. The actual people in the logical entity varies over time. Over the years as ownership has broadened, there is a strong overlap between shareholders and all employees, rendering the distinction moot. But not entirely so. The graph below shows how this 25% profit interest influences total profit distribution. Blue lines show how profit would be distributed if it was purely through shares. Green lines show the actual distribution of profits as determined by shares and profit-sharing. The 16 shareholders who have greater than 1% of the company are shown individually. The blue/green cluster on the right side of the graph represents the 23 shareholders who have less than 1% of the company each. The final green data point represents the profit distributed to non-shareholder employees. Clearly, for small shareholders and non-shareholders, the 25% profit sharing is significant.

This dual system is historic and very difficult to refactor to a shares-only system.

Implementation

Use shares, not percentages

While LLCs most commonly use percentage ownership, a system of shares is perfectly allowed. Switching to shares, and creating an initial total share count of 1,000,000 allowed us to stick with integer share count and avoid carrying six significant digits on percentages. That’s nice when you’re doing frequent transactions.

It’s also psychologically better (and simpler) when you activate shares to sell quarterly through the ESPP. No one’s share count decreases when this happens, though the percent of the company they own decreases. Since everyone is in effect selling shares pro-rata during these ESPP purchases, I don’t consider it dilution. Using percentages that change every quarter falsely reinforces this view that has negative connotations.

Responsibility for extending offers

Don’t compromise your standards (or your gut) for expediency’s sake. Politically expedient horse trades or special arrangements have occasionally caused me regret.

If you are selling your own shares, as I have been doing, you have to feel good selling; you should make decisions you feel good with, on terms you’ll be appreciated for, for the long-term.

Have clear criteria, apply consistently

We’ve maintained clear standards, similar terms, and generally consistent timing and offers over the last 7 years. Evidently we didn’t communicate these effectively as there seems to be more confusion and/or resentment than there should be given the facts and history.

I have made exceptions to the general pattern when it helps someone participate (loan terms), or when we were struggling to establish our Ann Arbor office (timing). In hindsight, I’d stick to standard terms for financing, and I’m glad I made earlier offers for Ann Arbor Atoms, as I think it helped create engagement at a critical juncture. Offers to very young Atoms did not work out.

Not a performance evaluation tool

If at X years you don’t want to extend an ownership offer to someone, you probably have a performance management problem that you’ve been ignoring. This isn’t to say that everyone needs to participate in the offer, but finding yourself unwilling or uncomfortable to extend an offer at X years is a bad sign. Our X is 5 years. Another company I know with a similar program has an X of 3 years.

Schedule of offer rounds

It would be helpful to standardize the timing of annual offers. (ESPP purchases happen automatically on quarter boundaries.) With a known tenure for eligibility (our 5 years), purchasers could save and plan for down payments, and company staff that executes the offers could schedule the workload. I didn’t do this.

Keeping track of transactions

We initially kept track of share transactions, ownership, and purchase price in a simple spreadsheet. As the number of offerings grew, and as the shares of departed shareholders were repurchased, sometimes pro-rata by all shareholders, this became unwieldy. With our 10 year vest for capital gains it was very important to know when shares were purchased, and for how much. Mike Marsiglia built a simple app (CRUD operations on top of a transaction log) that can generate a current cap table, transaction history, and share cost report.

Plan for the work

Invest the time to set up documents for repeated use. There are a lot of them. Some information (historical financials, cap table, etc) change on every offer. Arranging documents to make it easy to update on every offering pays dividends over time. Unfortunately, each offer always felt urgent to me (see above about scheduling), and the time required to produce a robust document system was important but never urgent. Don’t underestimate the time required to do an offering round. There are a lot of decisions to make, and, if you’re like me (see above on consistency) people to consider helping through exceptions to loan terms.

Legal

Legal entity form

I believe it’s been an important part of our ownership plan that shareholders are legal owners of the company. Since we’re an LLC, that means they are members of the LLC, with all the corresponding rights and privileges. It also means that we’re limited to 100 shareholders. That limit may be extended in the future. Another limitation of a Michigan LLC is that all members of the LLC must live in the same state.

Since every shareholder is a member, every shareholder gets a K-1 in tax season. When our K-1s are delayed due to circumstances beyond our control, every shareholder’s tax return is potentially delayed. If Atomic makes a mistake or amends a tax return, that may ripple through K-1s and have an effect on a lot of shareholders.

Since we’re all members of the LLC, changes to our operating agreement and some share re-purchases have required sign-off by all shareholders.

Receiving K-1s and signing legal documents can be a hassle, both for the company and the shareholder, but they also serve as very real reminders of the ownership interest, rights, and responsibilities of all shareholders.

Non-compete

If you don’t already require non-competes of employees (we don’t), you might need to consider adding that for at least significant shareholders (we do). While I didn’t like doing this, I ultimately felt it was the fair thing to do to protect all shareholders.

Handling re-purchases

Our 10-year vest for capital appreciation has worked as intended. It rewards long-term shareholders, hasn’t locked anyone in with golden handcuffs, and keeps the emphasis on the dividend as the primary shareholding financial benefit.

Retaining control over shares when shareholding employees depart the company is absolutely critical. Flexibility in the buyback process has been very useful to us, as we have exercised each of our four options at various points in time.

When purchasing un-vested shares back from departing shareholders, the purchaser sometimes received a bonanza in that the purchase price was below the current valuation, sometimes substantially so. The decision about who received this bonanza fell primarily to me for 10 years, and thus also the occasional thanks, more commonly a lack of appreciation, and sometimes resentment for lack of opportunity. In hindsight, I wish I’d not tried to solve each of these problems fairly or strategically and simply destroyed the shares, forcing all share purchases to happen at the current valuation, and all buybacks to benefit every shareholder pro-rata. It was a largely thankless and frustrating set of optimizations I attempted that I’m not sure gained the company anything.

Taxes

Retained earnings

Pass-through entities like LLCs and S Corps have a challenge with retained earnings. Shareholders are apportioned pass-through income (via K-1s) based on earnings, whether those earnings are retained or distributed. This is a critical distinction come tax time, as shareholders owe tax on all earnings, whether distributed or retained. Operating agreements usually specify minimal distribution amounts to at least cover the tax bill shareholders will experience, though that bill depends on individual tax circumstances, making it difficult to set the amount fairly for a large group of shareholders with varying tax rates.

First time, significant shareholders may also be at risk for penalties come April. Safe harbor rules and estimated tax payments are likely new to many people in a broad ownership plan like ours. We educate shareholders regularly on the subject.

Tax policies impact value

Our valuation is done by taking the post-tax worth of the expected future profit stream. When tax policy changes, as it did significantly in 2018, it impacted our valuation. We found it challenging to adjust our valuation for the changes in the tax code.

Installment sales versus redemption

In the first seven or so years of our plan, as I was wanting to decrease my holdings, and other Atoms were wanting to increase theirs, the company redeemed my shares and then sold the same number to the other Atom. This left me with a capital gains tax bill on the full amount of the transaction, even though I was financing the transaction and only received the downpayment amount at close.

In recent years we switched to me selling shares directly to another Atom. This let me treat these transactions as installment sales. I only owed capital gains tax on the actual amount of money I received in any given year. Stretching out the payment of capital gains tax was obviously beneficial to me.

Tracking loan types

When we switched from redemption to installment we created another bookkeeping burden, as the principle and the interest on these two types of loans, sometimes to the same person, had to be reported differently.

- Attention: Spending Your Most Valuable Currency - February 10, 2022

- Slicing the Revenue Pie in a Multi-Stakeholder Company - July 30, 2021

- Commercial versus Existential Purpose - July 19, 2021

- How I Misunderstood Mentorship and Benefited Anyway - June 16, 2021

- Sabbath Sundays and Slow Mondays - June 4, 2021