Editor’s Note: Since this post’s publication, Atomic has refined its approach to our “Rainy Day Fund.” Keep checking in on Great Not Big as we continue to tinker with and better our model.

Cash is the life blood that runs a business. If it’s mismanaged, it’s highly likely that the company will experience pain. Unfortunately, employees are often surprised by this pain, leading to negative FUDA.

Managing cash flow in a small company is a challenge, requiring financial understanding, discipline, modeling skills, and planning. But sharing and contextualizing cash flow broadly within your organization takes this challenge to the next level. It’s impossible without a lot of data, education, and trust.

Why We Share

At Atomic, we run an open books business. Instead of shielding people from the financial dynamics of the company, we’ve decided to educate them and share data.

It’s starts with a class for new hires called The Economics of AO, reinforced when we share and explain our company results every quarter. This gives employees the big pictures.

A few years ago, we also decided to share cash flow information, but in a way that didn’t overwhelm people. We believe in sharing our cash situation with shareholders for two main reasons:

- The transparency forces managers to be accountable for cash flow decisions.

- Shareholders are exposed to the data and are expected to responsibly engage and help if called upon.

How We Share Cash Flow Data

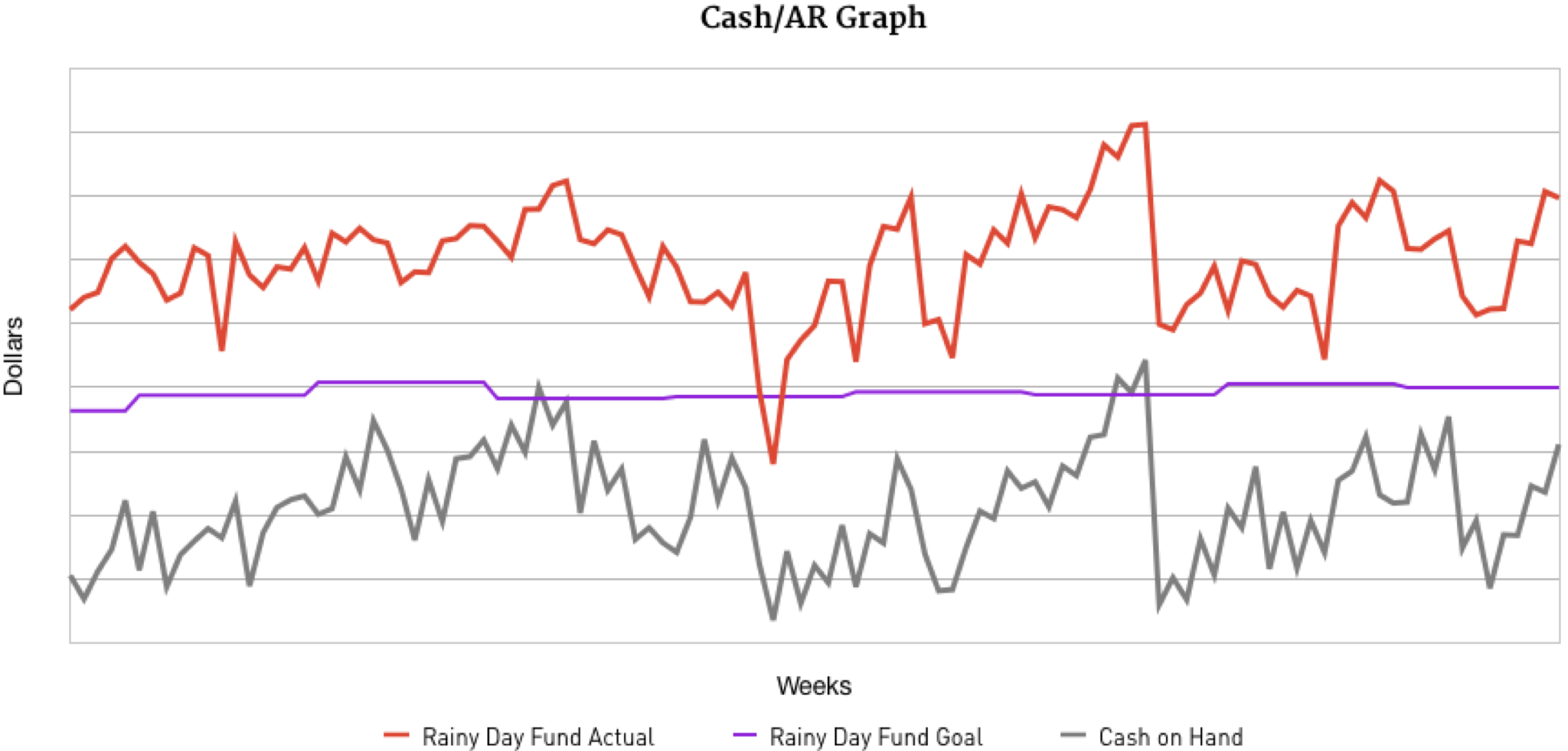

To simplify things, we created a high-level line graph called our Cash/AR (Accounts Receivable) report, which we share with all company shareholders. At the time of the post, about 63% of Atomic employees are shareholders, so the report is widely distributed.

This graph is based on the following simplifying constraints:

- AR will convert to cash at some point in the future. We do good work and do business with honest people. Over our 16 year history, we’ve had very little bad debt.

- We send invoices at a normal cadence (e.g. every 2 weeks). Invoices and their corresponding AR are coupled to time spent not necessarily project deliverables.

- In most cases we have sane payment terms. Our AR converts to cash in a timely fashion.

- The graph only shows what has happened, not what is about to happen. In a non-seasonal business like software design and development consulting, the past tends to predict the future. This certainly does not replace the need to develop more sophisticated one-off future facing models if a future cash fluctuation is anticipated (e.g. a building project, market adjustment, etc.).

Our Cash/AR graph plots three primary components over time (x-axis). Each component is reported in dollars (y-axis). Depending on your cash flow philosophy or need, it may be valuable to plot other components as well (e.g. line of credit, etc.). For simplicity, I’m only going to focus on the major components.

The following shows roughly 2 years of weekly data.

This graph plots three different amounts:

1. Rainy Day Fund Goal (RDF Goal)

Saving for a rainy day is an important aspect of running a responsible business. The art of setting the RDF Goal is unique to each organization. We’ve adjusted our goal over time based on factors like the size of our team, diversity of client base, willingness to leverage our line of credit, etc. We’re currently using an algorithm that adjusts our goal based on real company costs each quarter. You can see these small quarterly adjustments in the graph.

The most important thing to point out is that our goal is the combination of both cash and AR. Cash is very noisy, but our workload is steady. We’ve found that targeting the combination of cash and AR brings consistency to the data, and helps us avoid unnecessary panic.

2.Rainy Day Fund Actual (RDF Actual)

The RDF Actual is the sum of actual cash and AR for a given date. We distribute profit (profit sharing and shareholder distributions) each quarter, and you can see the RDF Actual buildup throughout the quarter and then drop at the end of the quarter in the graph.

The saw-tooth noise throughout the quarter is representing expenses and invoicing cycles.

3. Actual Cash

The actual cash line represents the actual cash in the bank for a given date. The distance between the cash line and RDF Actual line represents the amount of outstanding AR. If actual cash is following the pattern of the RDF Actual then we know that AR isn’t growing or shrinking at an alarming rate.

Analyzing the Graph

The primary components of RDF Goal, RDF Actual, and Actual Cash graphed together over time gives a nice high-level view of the company’s health.

The graph allows you to quickly see and evaluate the following questions:

Are we consuming our rainy day fund?

If the RDF Actual dips below the RDF Goal line the answer is—yes.

The graph also gives you a good context of how much you’re consuming at any given time and how many occurrences you’ve dipped below the RDF Goal line in a given time segment.

What is my current cash on hand?

The cash on hand line shows your current cash and contextualizes it over time.

Is my AR converting to cash in a timely fashion?

The distance between the RDF Actual and the cash on hand line is the current AR.

Assuming your company size didn’t change:

- When the RDF Actual and cash on hand lines start to drift apart then your AR isn’t converting to cash in a timely fashion. You may be in for a short-term cash crunch.

- When the RDF Actual and cash on hand begin to merge together it’s a leading indicator for a potential future cash crunch.

Am I able to hold less cash in the company?

Maybe. We’ve been able to use the graph to quickly review our cash situation over time. This has helped us understand the peaks and valleys of our cash flow and adjust our RDF Goal.

This simple to produce and easy to maintain graph has provide a lot of ongoing value for our organization.