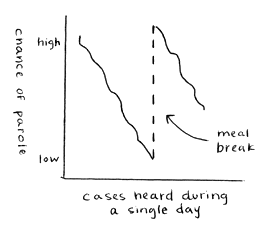

If you find yourself up for parole in Israel, you should pick the time of day you make your pitch very, very carefully. An article in The Economist back in the spring described a study of parole applicants and their chance of being granted parole as a function of the time of day the case is considered. The data clearly show you have a much lower likelihood of being paroled if the judge hearing your case is tired or hungry. The graph below (a simplified sketch as The Economist wanted $460 to use their graph) shows how incredibly strong this relationship is. The chance of being paroled decreases as the number of cases the judge has heard increases, and meal breaks reset the chance from being very low to quite high.

One of the questions addressed in the study was what explained the strong correlation between outcome and time of day. Was it the judge’s hunger or his fatigue that mattered more? The researchers found that the number of cases heard by a judge is more strongly correlated with denying parole than the judge’s blood sugar level. Making parole decisions is mentally taxing. The more decisions a judge has made, the more tired he becomes and the more likely he is to start looking for easy answers (in this case, to say “no” is easier, safer, and preserves future options). Making hard decisions, in other words, is fatiguing.

I was reminded of the article in The Economist when I came across an article on decision fatigue in the New York Times this weekend. It too describes the Israeli parole review study (in more detail), but it takes the explanation behind the phenomenon much further and explains an apparent linkage between decision fatigue and glucose levels.

Decision fatigue

Evidently I’m not the only one who is mystified by how tired I can be at the end of a normal work day. I don’t “do” much at work except make a bunch of decisions. Why should I sometimes be so exhausted? The concept of decision fatigue, that the very act of making decisions taxes the brain and wears us down, is not commonly known. Tradeoffs are the hardest decisions to make as they are the most complex. And that in turn describes my job quite well. It seems there are very few black and white or simple decisions I get involved in — most decisions consist of a set of less-than-perfect choices involving ambiguity and tradeoffs.

When your brain is fatigued from making decisions it starts to look for shortcuts. The two most common are to act impulsively or to do nothing. Impulsive decision making means not thinking through consequences. (The Times author gave a telling example: “Sure, tweet that photo! What could go wrong?”) Not deciding obviously has it’s own set of consequences and contributes to the other mental taxing reality of modern work life: a perpetually growing to-do list.

The mental effort comes from actually making decisions, not contemplating them or actually taking action. It’s more wearisome, evidently, to have to decide than it is to implement. Deciding shuts down future possibilities, exposes you to potential criticism, and, at least when you’re not decision fatigued, involves examining multiple choices and the tradeoffs and future impact of those choices.

One of the difficult aspects of mitigating risk from decision fatigue is that our bodies don’t show signs of it the way we do with physical exhaustion. When I bike too far or too fast my knee hurts and I’m winded. It’s pretty clear I’ve exhausted my capacity to bike further. Decision fatigue doesn’t manifest that way. We don’t get an obvious reminder to be careful, take a break, or defer important decisions.

Ego depletion

Decision fatigue is an example of a broader phenomenon called ego depletion. The idea of ego depletion (a name which I find strange, but evidently pays homage to Freud) is that we all have a finite store of mental energy for self-control. In other words, our willpower can be depleted.

Researchers have devised experiments and measured responses of people in the real world to study the link between decision making and willpower. It turns out that making decisions causes depletion of willpower. In turn, if your willpower is depleted, you’re more likely to make a decision that’s good in the short-term, but bad in the long-term. Once your willpower is depleted, you become less likely to thoroughly consider the complex tradeoffs some decisions require.

It’s been known for a while that glucose can reduce or even eliminate the effect of ego depletion. (I once knew a project manager who always brought candy to meetings. Turns out to be a smart thing to do.) But it’s also known that the brain uses the same amount of energy regardless of what a person is doing. So how can glucose combat decision fatigue?

When you’re in a state of depletion, the portion of your brain that’s involved with rewards is more active than the portion of your brain that’s involved with self-control. As a result you’re more likely to make decisions for the short-term that provide immediate pleasure, and less likely to make long-term decisions that might in fact be better, but are harder or more painful in the short-term. For some reason, a dose of glucose reversed this phenomenon and reactivates the self-control center. Eat that candy and, bingo! you’re back to making good decisions.

Glucose, evidently, and simple rest, presumably, can reverse the effects of decision fatigue in the short-term. What, I wonder, about the long-term? I know there have been periods in my work life when I feel what I suspect is the cumulative effects of weeks or even months of decision fatigue. This was something that neither a meal nor a weekend could fully ameliorate. I haven’t found anything written about longer term depletion, but it strikes me as a fruitful course of research.

Applying this knowledge

As I read the article in the Times I thought of several things I see at work which either respects or ignores the realities of decision fatigue. Here are a few:

- We should be wary of asking customers to organize and prioritize a large backlog of stories, especially when they have less budget than stories. Choosing between features because you can’t have them all is perfect example of decisions involving complex tradeoffs.

- Don’t skip lunch to get more work done. And be sure you start the day by eating breakfast.

- If you spend all day making hard decisions, your chance of exercising after work is small, presuming that doing so relies on your self-control. Plan accordingly, or exercise before work.

- The Extreme Programming ritual of providing snacks for the team suddenly makes even more sense.

- Breaks should be strategically inserted in the middle of longer work sessions and involve calories.

- Project scheduling, software design, architecture planning, sales triage, capacity planning, and estimation are likely to be activities which are particularly taxing and cause decision fatigue.

- Scheduling difficult decision work for the end of the day is probably nuts.

- Asking your boss for a raise just before lunch or at the end of the day; ditto.

- We’ve evolved a hiring process that culminates in a giant standup meeting debrief at the end of the interview day. Everyone who talked to the candidate participates. Smartly, as it turns out, we don’t allow ourselves to make a decision at the debrief.

- Sometimes I’ll make a decision under circumstances where I’m likely depleted, so I’ll label it as preliminary and select a fixed time the next day to review it and finalize. This seems like a good technique.

Conclusion

The Times author concludes by observing that people aren’t good or bad decision makers. Instead, the ability to make good decisions fluctuates over time in all of us. Just because you generally make good decisions doesn’t mean you’re not susceptible to decision fatigue. (As a generally good decision maker who’s prone to ocassionally make some pretty boneheaded ones, I relate strongly to this idea.) Instead of counting on your willpower to remain strong all day, and hence your decision making abilities, it’s better to conserve your willpower so you’re not in depletion when a really important decision or an emergency arises.

As a preeminent researcher in this field (Roy Baumeister) states, “The best decision makers are the ones who know when not to trust themselves.”

- Attention: Spending Your Most Valuable Currency - February 10, 2022

- Slicing the Revenue Pie in a Multi-Stakeholder Company - July 30, 2021

- Commercial versus Existential Purpose - July 19, 2021

- How I Misunderstood Mentorship and Benefited Anyway - June 16, 2021

- Sabbath Sundays and Slow Mondays - June 4, 2021

Marina

August 24, 2011Fascinating! My mother used to send a bar of chocolate to school with me on test days. She claimed the brain needed it for optimal performance. My husband has been poking fun at that for years. I feel vindicated. :)

Carl Erickson

August 25, 2011It is fascinating, I agree, Marina. Your mom had more science behind her caring than she knew.

Rob VS

August 25, 2011I expect that anyone who’s built a house can relate to this really well. In the beginning, you consider every option very carefully – what plumbing fixtures do I want? What style of trim? etc. By the end of the process, you’re just about ready to let the general contractor choose for you.

Thinking about this in a more devious manner, one could use this to their advantage. For example, in a meeting where several decisions need to be made, it would be wise to first address the items that you care about the least and others presumably care about more. This way, at the end of the meeting, the others are more fatigued and are thus more likely to acquiesce to your desires.

Carl Erickson

August 26, 2011Great example, Rob.

I suspect crafty sales people think exactly about what you observe. They NY Times article describes some experiments with how automobile options were presented that support this.

stevepoling

August 31, 2011The book “Predictably Irrational” explores some of these ideas. Likewise the book “Switch” cited the depletion of will-power. Henceforth, I’ll be sure to bring sweets to meetings with stakeholders.

Usability Testing Field Notes | Atomic Spin

January 19, 2012[…] up. Carl shared some interesting information about the impact that food has on our mental state in this post. While the situation he describes is slightly different, the principles are the […]